Jenny McLeod at 80: “to me I’m always me…”

I’ve known Jenny McLeod since the late 1960’s as teacher, colleague and friend. This article about her life and work is my 80th birthday tribute to one of New Zealand’s most brilliant, inventive and mercurial composers.

At the recent Martinborough Music Festival Jenny McLeod’s string quartet Airs for the Winged Isle had its premiere performance. Written in 2009, it is dedicated as “A little Skye suite in memory of John MacLeod of MacLeod, Dunvegan (1935-2007) 29th Chief of the Clan MacLeod - with affection and respect for a prince of a man.” The droll programme notes for the ten miniatures tell of a heavy-hearted MacLeod putting the flat-topped Black Cuillin mountains (also known as “MacLeod’s Tables”) on the market to raise funds to repair the roof of Dunvegan Castle. There was no sale and for the 10th movement the composer offers a picture of MacLeod “muttering ancient prayers and imprecations to ward off the rain” and frantically rushing around his castle setting plastic buckets under leaks.

Musically the work, like its text, is full McLeod’s joyous humour and unpredictable wit. We hear the skirl and drone of the bagpipes, the insistent rhythms of the fiddles and through it all the clever writing and musical surprises that are always part of McLeod’s compositions, whatever the style. I don’t know why these Airs waited so long for their premiere but I’m keen to hear them again soon.

This week Jenny McLeod turns 80. My first strong memories of her are from 1968 when, with Gordon Burt and composers Lyell Cresswell and Denis Smalley, I was part of a small music analysis Honours class she taught at Victoria University. McLeod was 26 and not long back from the heady worlds of European contemporary music and composition studies with Messiaen, Boulez and Stockhausen. An inspiring and unconventional lecturer, she drove an untidy VW Beetle and we often crammed into it to head off to the rocks at Oriental Bay or, if raining, to the bar of the old George Hotel on Willis Street. In these unlikely classrooms we delved with almost obsessive enthusiasm into the serial intricacies of the 2nd Viennese School.

In Europe McLeod had picked up on an idea of Stockhausen’s to compose a piece around accelerandi and ritardandi. In For Seven, a chamber work she described to me once as her “high European effort”, she developed musical material mathematically. “I worked it all out with graph paper; and then I wanted more colour, so I put background music behind the accelerandi and ritardandi in the foreground and had the background emerge from time to time.” For Seven, which now sounds very French in its timbres and includes marvellous bursts of woodwind birdsong, was first performed in 1966 in Cologne at the end of Stockhausen’s course. The ensemble included some of the biggest names in European contemporary performance, including percussionist Christoph Caskel, cellist Siegfried Palm and pianist Aloys Kontarsky. After McLeod left Europe Bruno Maderna directed more performances at Darmstadt and the Berlin Festival.

It was over two decades before McLeod heard For Seven again, as invited guest composer at a 1987 festival of contemporary music in Louisville, Kentucky. That visit to the States was a career watershed for a composer in creative despair – but what had happened in the intervening years?

In 1968 a group of us, students from the Music Department at Victoria, piled into a van and travelled to Masterton for the premiere of McLeod’s Earth and Sky. To sustain herself while writing For Seven during what she described later as “the black depths of Cologne”, McLeod had read and re-read Richard Taylor’s translations of Maori creation poetry from her copy of Allen Curnow’s Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse. Back in New Zealand, invited by a branch of the NZ Educational Institute to write a work for 300 Wairarapa primary school children, she devised her own text from those translations and created Earth and Sky, a hugely ambitious work of “music theatre in three acts” for multiple choirs, brass, woodwind and percussion orchestras, pianos, organ and tape.

Jenny’s McLeod’s theatre piece Earth and Sky

“…a sensation.”

The production was a sensation. More performances followed, including one in Auckland in the presence of Queen Elizabeth II which was recorded for commercial LP release. Some parts were played by adults but most by children. When we asked McLeod how the young musicians had coped with the complex rhythms and textures of her dynamic score, she said airily, miming with invisible drum sticks, “I just said ‘it goes like this’.”

The even bigger Under the Sun (1971) for Palmerston North schoolchildren was ultimately less successful. “You can’t repeat yourself,” she told me in 1988. “I’m dissatisfied with a lot of the music in it.” But the production led her to new idioms. “There was a rock group in it and one night we got into a jam session. I’d never improvised. We went on till 3 or 4am and I felt completely refreshed.”

McLeod was by then Professor of Music at Victoria University, appointed at the remarkably young age of 29 to a role she held for just 6 years. A year before her resignation in 1976 she encountered the Divine Light Mission. “One of the Indians came to talk in Wellington. And so, we bowled along and I just got zapped!” She resigned from the university and remained involved with the Mission for several years, writing pop songs, taking Indian drum lessons and developing her skills in improvisation.

Another apparent turning point came in 1981. Back from eighteen months in the States, McLeod said to me later that she had “met the spiritual scene head-on there and got pretty disgusted with it. I was being really dragged down. So, at that point I waved bye bye.” She left the Mission, moved to the house in Pukerua Bay that has been her home until very recently, and began accepting commissions again. The rock idioms remained in her music for a while, however, and in the soundtrack for the film The Silent One she combined largely tonal, popular writing with tuned percussion that brilliantly evoke the film’s setting in the Pacific Islands.

In 1987 McLeod wrote three very well-received works, two Rock Sonatas for piano and Music for Four for two pianos and two percussionists. This month Atoll Records will launch a new album including this appealing, energetic music. McLeod, however, was finding “the popular language I’d worked so hard to achieve turning out to be a dead end with very limited expressive potential. But fortunately, when you’re desperately in need of something, it comes along.”

What came along was the invitation to that Louisville festival. There McLeod met Dutch composer Peter Schat and his “Tone Clock” theories. After overcoming her initial prejudice against what she believed were “serial theories”, she realised that his “multi-coloured new tonality” and its “hours” could offer her a way forward. She followed him back to Amsterdam after America for several weeks of work together. It took her “right back into the obsession with symmetry in Earth and Sky and For Seven.”

One of McLeod’s endearing recent practices has been expressing herself in verse. “In my later years,” she told me recently, “poetry has become more attached to me. I don't like programme notes so I write a poem which embodies more about how I feel about a piece and gives people more choices.”

Perhaps her longest work in verse was created when she was invited to deliver The Lilburn Lecture in 2016, for the annual event on November 2nd, Lilburn’s birthday. She called her lecture “Prosaic Notes from an Unwritten Journal,” and illustrated a poetic and witty account of her life and career with excerpts from her music. In the Lecture, describing the impact of Schat’s “Tone Clock” theories she said:

“The whole chromatic world

seemed now to reveal itself as never before –

this time with a vast and bright appeal.”

Indeed, for McLeod the “Tone Clocks” opened a door to a new world of inspiration. Her first work to use the theory was a piano piece to mark the 60th birthday of composer David Farquhar in 1988; more Tone Clock piano pieces followed, the fifth subtitled Vive Messiaen! and written for the French composer’s 80th birthday. Messiaen called it an “exquisite idea.” Nos 8 -11 marked Lilburn’s 80th birthday in 1995, Nos 13 -17 came later for Jack Body’s 60th, commissioned by Dr Jack C. Richards, and No 18, Landscape Prelude, was commissioned in 2007 by pianist Stephen de Pledge as part of a set from twelve different New Zealand composers.

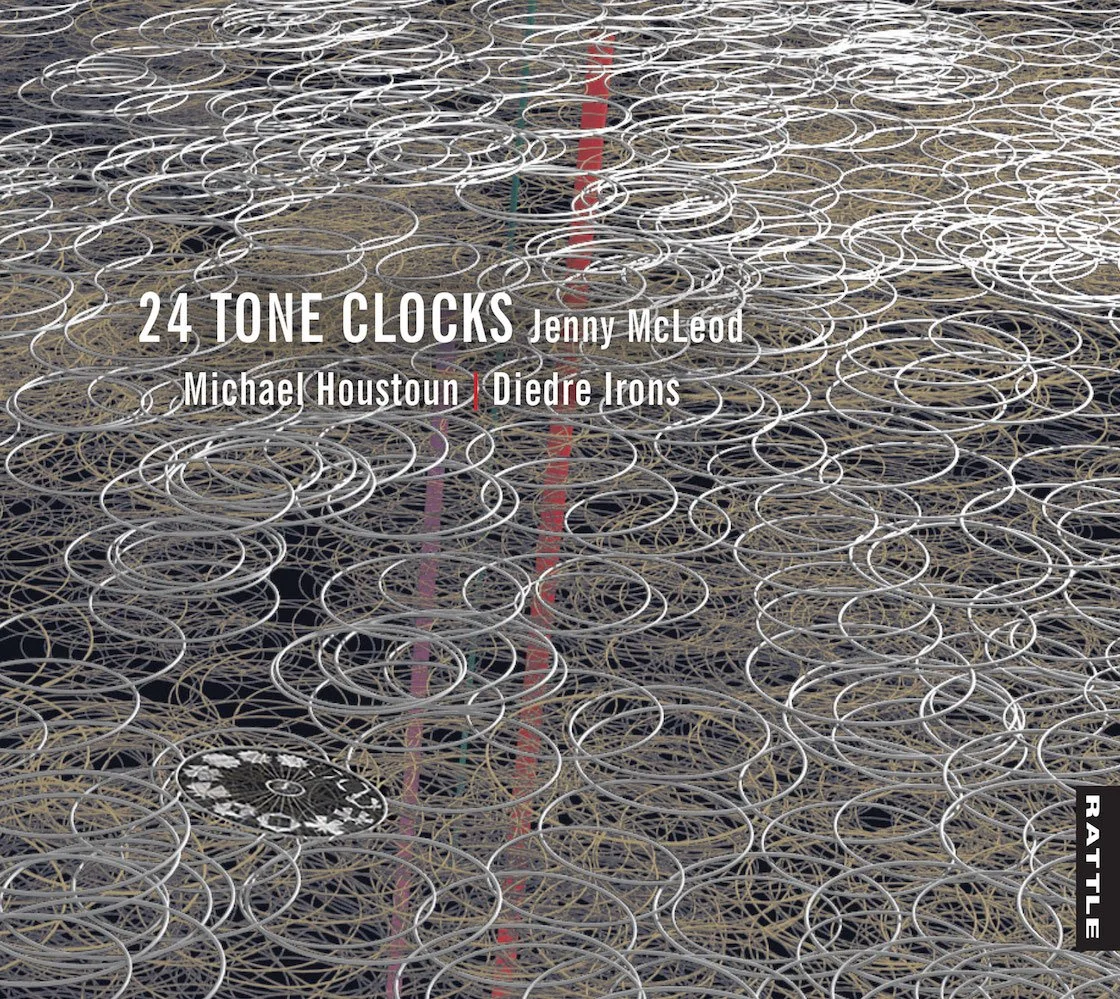

24 Tone Clocks by Jenny McLeod

“…beautiful and luminous explorations of piano timbre. “

In 2011 pianist Michael Houstoun commissioned six more Tone Clock Pieces from McLeod and he and pianist Diedre Irons recorded the full set of twenty-four for a handsome two-disc album released for her 75th birthday in 2016 by Rattle Records. These works have a detailed theory behind them, set out in excellent sleeve notes. But like For Seven they also draw on the natural world. “Of course there is birdsong in Messiaen’s piece”, she says, and she was also inspired by the “high sky/wild crags and rocks” of her Pukerua Bay seaside view. “Living by the sea” she said once, “you become part of it somehow”. The twenty-four pieces are also beautiful and luminous explorations of piano timbre.

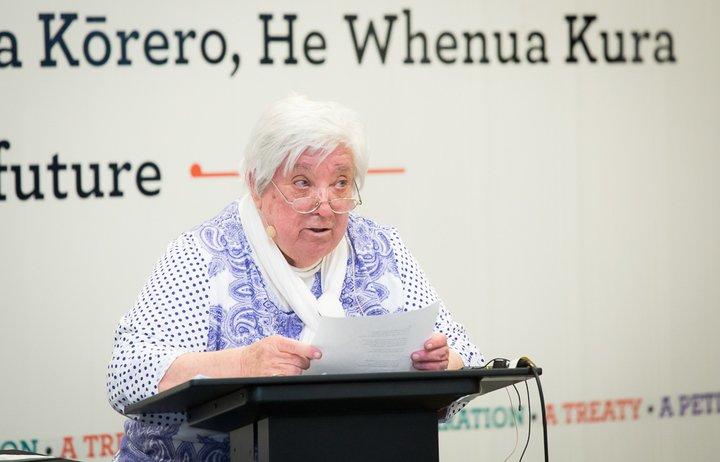

Jenny McLeod

delivering The Lilburn Lecture in 2016

In her Lilburn Lecture McLeod asked, with characteristic humour, “"Do I really have a 'Voice'? Don't ask me! - to me I'm always me...". She didn’t refer directly in the Lecture to a community that became very influential in the 1990’s to her music, life and identity. Responding to the NZ Choral Federation’s bi-cultural intentions for the “Sing Aotearoa” Festival in Ohakune in 1993, she scored her commissioned He Iwi Kotahi Tatou for large choir, Māori choir, chamber choir, marae singers and two pianos. Through this work began McLeod’s close association with Ngāti Rangi, tangata whenua of the Maungarongo marae at Ohakune. The central part of He Iwi was based on an ancient waiata tangi belonging to Ngāti Rangi. McLeod formed a close friendship with kuia Joan Akapita, who invited her to join the iwi’s annual canoe trip down the Whanganui River. The only Pākeha amongst 110 paddlers, she felt privileged to join what she described as “a wananga, for spiritual learning.”

McLeod’s friendship with Akapita and others within Ngāti Rangi led to her adoption as a member of the devoutly Catholic Maungarongo whanau, and a regular role as choral judge for Katorika Hui Aranga, the annual Easter hui and choral competition held by Māori Catholics of New Zealand. Over many years she composed an annual four-part hymn in Māori for the competing choirs, learning te reo Māori in order write her own words. In 1996, she also began work as librettist and composer for her opera Hōhepa, honouring the request by Matiu Mareikura of Ngāti Rangi for her to write the story of Hōhepa Te Umuroa. The work was premiered at the NZ International Festival of the Arts by NZ Opera in 2012.

McLeod said twenty years ago “people looking from the outside probably think I’ve gone like a blinking zig-zag, backwards and forward my whole life long. I don’t care what they think. It looks different from the inside.”

McLeod’s works over the past two decades, many in response to commissions, do indeed have much in common with her earliest works. Two recent piano trios, Bright Dark Night commissioned and premiered earlier this year by the NZ Chamber Soloists and Clouds, scheduled for premiere next week by the NZTrio in a concert and live-stream, combine her extraordinary composing skill, humour and wit with the commitment to structure and form that created For Seven and the Tone Clock pieces. We find as well inspiration from the spiritual and natural worlds and her abiding interest in the expressive use of colour. The sharp musical intelligence that inspired us as students in 1968 is still at work, and her sense of humour and infectious chuckle are often present.

Housebound in recent years by ill health, McLeod is nonetheless delighted that her 80th birthday will be marked by performances of new and older works and that scholars are currently working on publications of both her theoretical writings and a book about her life and work. A few days ago she sent me an email with the note “something came over me” and this poem:

Mysteries?

i

if ever I said

music could be seen

as a sort of heavenly oneness

I was talking about me

and not exactly about music

necessarily

especially not today

when bits of it can be found

floating round all over the place

and it might even be me

singing them

said Pooh

ii

honestly

let’s put it on the wall

to remember

as I was saying

anything we choose

can apparently

magically

represent (or stand for)

anything at all, that is,

anything else we choose

(are we still awake?)

I mean, if we do so choose

but it doesn’t have to

thank goodness

iii

(and I love this bit best)

concerning anything everywhere

none of it needs to be

anything more than itself

whether real or ideal

or any mixture of the two

said Pooh

with his usual

remarkable assurance

iv

Oh. whatever we might

or might not feel

could be missing,

sadly missing

from the honey-pot

said Pooh

we can still all

just be ourselves

and not worry

Jenny McLeod “Portrait with Piano” album was released in late 2021 (Atoll) and you can read my Album Review here

NZ Trio “Dramatic Skies 2: Cumulus” including Clouds by Jenny McLeod Auckland (and livestream) 16 November

Stroma: 20th Birthday Concert including Cat Dreams by Jenny McLeod Wellington 23 November