Lyell Cresswell: a personal tribute

“To express the painful feelings aroused by the death of a friend is very difficult and all too frequently necessary. For most, the attempt to disentangle the inner turmoil and the struggle to express it is beyond the scope of words.” (Composer Lyell Cresswell in the lecture “Tracing the Lightning Flashes” in 2000.)

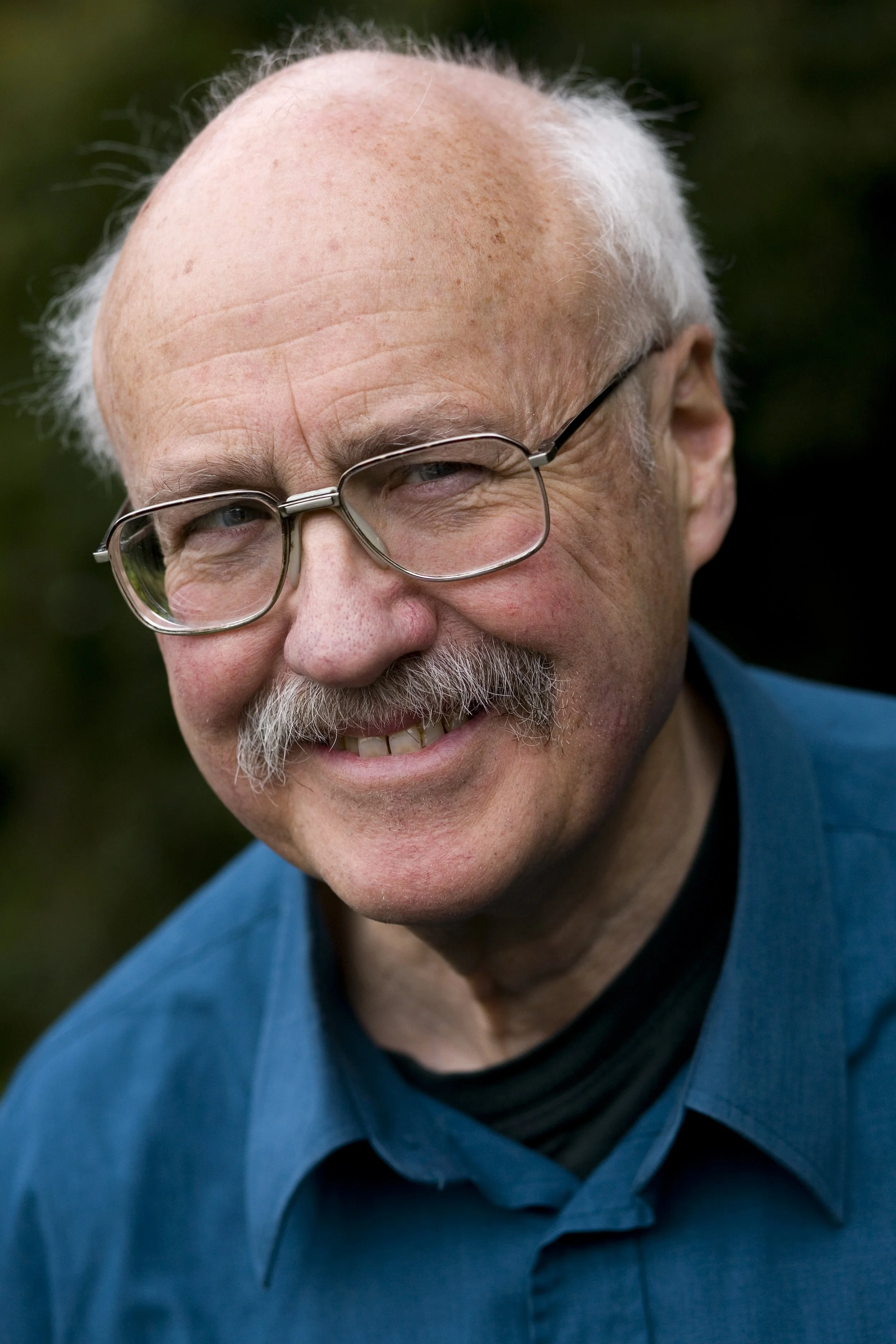

Composer Lyell Cresswell (1944-2022)

Photo credit: Gareth Watkins

On Sunday 20 March this year I was scheduled to record a conversation with my old friend, composer Lyell Cresswell, for SOUNZ. Lyell had been diagnosed with terminal liver cancer and been told he had only months to live. His family and friends in Edinburgh, where he’d lived since 1985, said he was keen to have the conversation about his life and music and I was looking forward to talking, perhaps for the last time, to my dear friend. To deal with the time difference, the call was scheduled for 7am (NZ time) that Sunday morning, 6pm in Edinburgh on 19 March.

SOUNZ dropped off a microphone/recording device and I prepared questions. I lay awake wondering if he was well enough for this – he was just home from hospital - and also whether I could make the microphone device work adequately for a cellphone call. I got up early and then the message came. Lyell had sadly died an hour earlier.

I was blind-sided. Unable to do much that day, I communicated the news of his death to his many friends and colleagues, musicians and composers, who were as shocked and saddened as I was.

Later, a message from his devoted niece Miriam Meyerhoff with a description of his last afternoon helped. Good friends had gathered at his bedside in the home he and his wife Catherine had lived in in Edinburgh for decades, which I’d visited and stayed in several times. He was in the living room, surrounded by artworks he treasured, a friend had played him a recent recording of one of his works, and he died peacefully, holding the hand of Catherine, his beloved wife of fifty years. He’d contracted COVID while in hospital and this hastened his death, taking us all by surprise.

I first met Lyell in 1965. I was 17, he was 20, and we were both enrolled in Music 1, as it was called, at Victoria University of Wellington. We were friends for the four years of our studies at Victoria and remained friends for the next 53 years. We shared similar memories of those student days - the idiosyncrasies of Freddy Page, professor and head of the Music Department and a huge advocate of contemporary music, and Jenny McLeod’s extraordinarily stimulating Honours Music Analysis class in our fourth year. We both sang in the University Choir and the newly formed Bach Choir under our mutual friend, the late Tony Jennings, a marvellously talented musician who introduced us to “Bach with a bounce.”

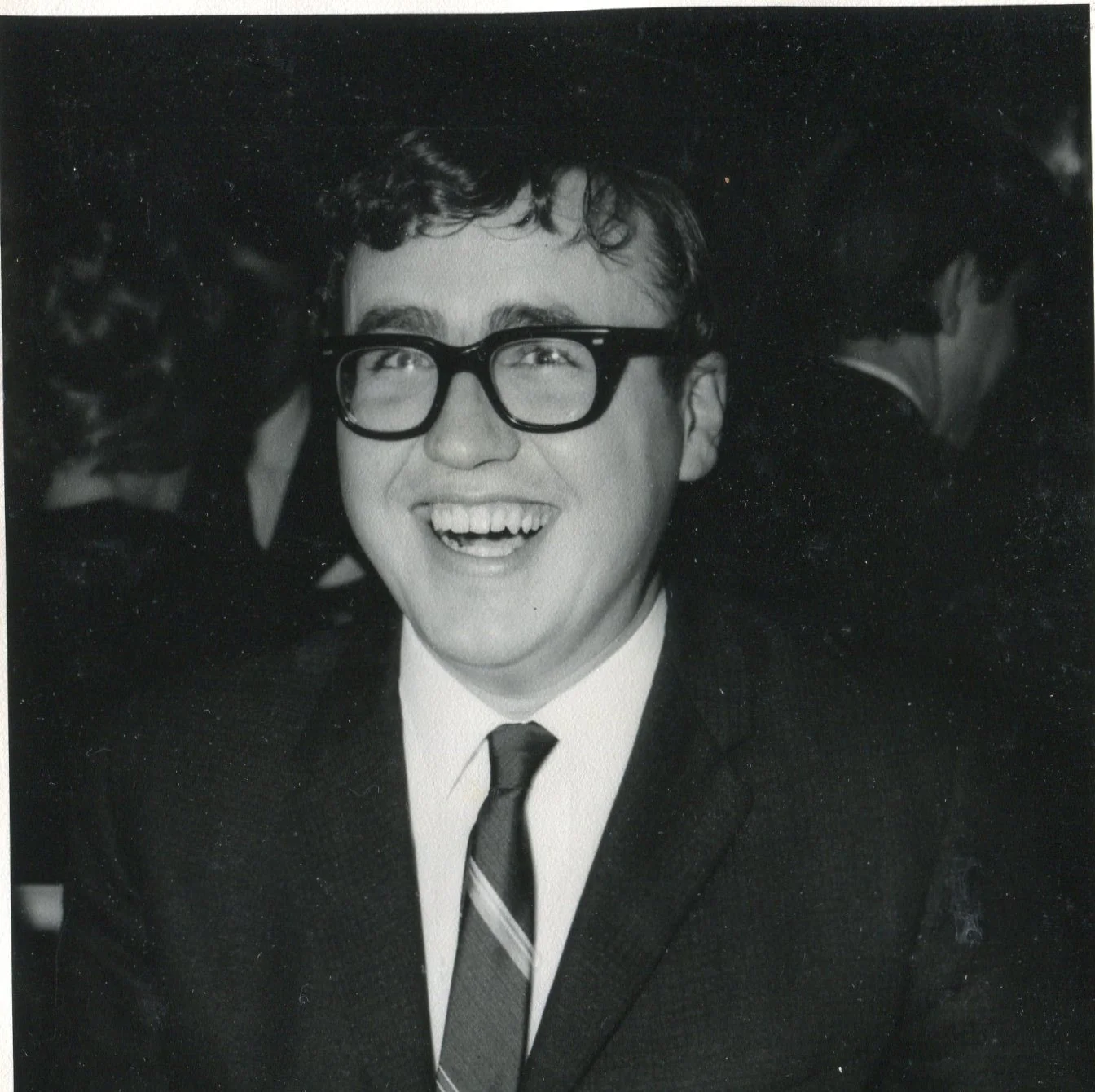

Lyell Cresswell in the 1960’s

…performing in a Salvation Army Students’ Fellowship revue.

There was always laughter around Lyell – he was indeed the funniest person I’ve ever known. He and I organised a somewhat disrespectful Granville Bantock Festival in 1968 at the Music Department to mark the centenary of the birth of this obscure (to us at least) English composer. Who knows why we included a piece called “Fire! Fire!” by Ezra Read, a contemporary of Bantock’s? Lyell (who was not a pianist), played the fast-moving piano part admirably and I declaimed the humorous narration we’d put together from score annotations. There was even a sly reference to Douglas Lilburn’s pioneering electronic work The Return. “And again (imitating the tones of Lilburn’s narrator Tim Eliot in the opening line of Alistair Campbell’s poem)...the engines were on the road.” Looking back, I suppose the event illustrated Lyell’s absurdist leanings. At the time, it was great fun.

Lyell Cesswell in 1969

…after a graduation ceremony at which he was awarded a Bachelor of Music with First Class Honours in composition.

We were both in Toronto in 1969, Lyell studying composition while I was teaching high school music classes, and though we didn’t meet for many years after that we kept in touch, some years with just the annual Christmas card. Whenever he came to New Zealand for performances, my partner and I caught up with him and Catherine at concerts and in recent years over lunches in Waikanae and dinners at Italian restaurants. I remember a hilarious game of foosball (table soccer) at Scopa in Wellington a few years ago. And when my work or travel took us to the UK, he and Catherine were always generous hosts - we stayed with them in Edinburgh several times, ate porridge for breakfast and met the latest black-and-white cat.

Lyell’s music was as unique and unexpectedly colourful as his personality. The influence of his Salvation Army background was strong; he grew up playing the trumpet and often featured the brass section in his orchestral textures. I have strong memories of the premiere of O! for orchestra, played by the NZSO in Wellington Town Hall in 1983. Commissioned to mark the 100th anniversary of the Salvation Army in New Zealand, it is based on the Army tunes ‘Oh boundless salvation’ and ‘Are You Washed in the Blood of the Lamb?’ “The nature of the piece,” wrote Lyell in the programme note, “is that of an exclamation”. The powerful and fearless simplicity of his forthright orchestral gestures and the bursts of orchestral colour were a surprise to me then, and are features of a number of his big works including Salm and A Modern Ecstasy.

When Lyell wrote The Clock Stops with New Zealand poet Fiona Farrell in 2014, the work, created with the devastating Christchurch earthquakes in the background, was premiered in an NZSO programme conducted by his younger Scottish composer colleague, Sir James McMillan. The programme also included McMillan’s works Woman of the Apocalypse and The Confession of Isobel Gowdie.

I interviewed both composers for a Listener story before the concert. McMillan, who studied with Lyell in 1980/81, admitted that what he called “the apocalyptic effect” of Lyell’s music had been an important influence on his own composing approach. When I passed this on to Lyell, he was quietly amused. “Ah, the “apocalyptic” effect!” he said, ironically and without further comment.

Lyell wrote numerous instrumental concertos, commissioned, like most of his music, for specific performers or occasions. I recall the New Zealand String Quartet playing his richly textured Concerto for Orchestra and String Quartet with NZSO in 2012. The work’s premiere had been in Aberdeen years earlier and the NZSQ first played it with the BBC Scottish Orchestra in one of two festivals Lyell organised in Edinburgh called “New Zealand New Music”. He lived in Scotland but always considered himself a New Zealander and was keen to promote the work of his compatriot composers.

Lyell Cresswell and the author in Edinburgh in 2015

…he lived in Scotland but always considered himself a New Zealander.

Dragspil, a concerto for accordion and orchestra, was commissioned by the BBC Proms and premiered in 1995 by Scottish-born accordionist James Crabb and the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra. Crabb, possibly the greatest living exponent of his instrument and now based in Australia, told me a few years ago that he would love to play the concerto in New Zealand. “Lyell’s a fantastic composer and such a delightful man,” he said. “But he’s one of those people who doesn’t push himself forward.”

The title is Icelandic for accordion. Lyell described Dragspil’s structure in a lecture. “The overall shape of the piece is in folds like the bellows of the accordion. Perhaps,” he said, “this form could be likened to the use of tmesis – splitting the syllables of a compound word by inserting another. So a more illuminating version of the title might have been Drag-bloody-spil.”

It is some comfort to Lyell’s many friends and colleagues that his music remains for us to enjoy. There is so much – SOUNZ lists 125 works – and so many stories to go with it. The titles often use metaphor, conjure visual images or refer to literature or other art. The quirky humour is sometimes explicit in titles such as in Le Sucre du Printemps for 6 bass clarinets and 3 contrabass clarinets (we studied The Rite of Spring in depth with Jenny McLeod in 1968), Threnody for Mrs S who drowned at her baptism for orchestra, Soliloquy on a Lambent Tailpiece for clarinet, violin and double bass. But Lyell’s clever use of humour should not fool us into thinking that he was not also a deeply serious composer who expressed profound ideas and feelings in his music. “My music,” he told me once, simply, “combines intellect and emotion.”

When I turned 70 a few years ago, Lyell wrote a little piano piece for me. It became part of a set called Seven Little Piano Pieces, each written by him for a friend, colleague or family member to mark a significant birthday. There is a video of the first public performance of EK (for Elizabeth Kerr) here. It’s a gentle, affectionate little piece and, I like to think, written so that my ageing fingers will not find it difficult. I was deeply touched.

Lyell Cresswell

…his music combines intellect and emotion.

Photo credit: Gareth Watkins

So, goodbye, dear old friend. You were right, it has been a struggle to find words to express my feelings and I wish I could have done so, like you, in music. But thank you for your music, a priceless, unique and enduring gift. And for the splendid memories so many of us have of a clever, funny, lovable, loyal and always surprising man.

This tribute is not an obituary. I wrote one of those in the fortnight after Lyell’s death and you can read it here. It includes details of his life and music and the many awards, honours and prizes he won during his remarkable career.