Shostakovich: music for troubled times

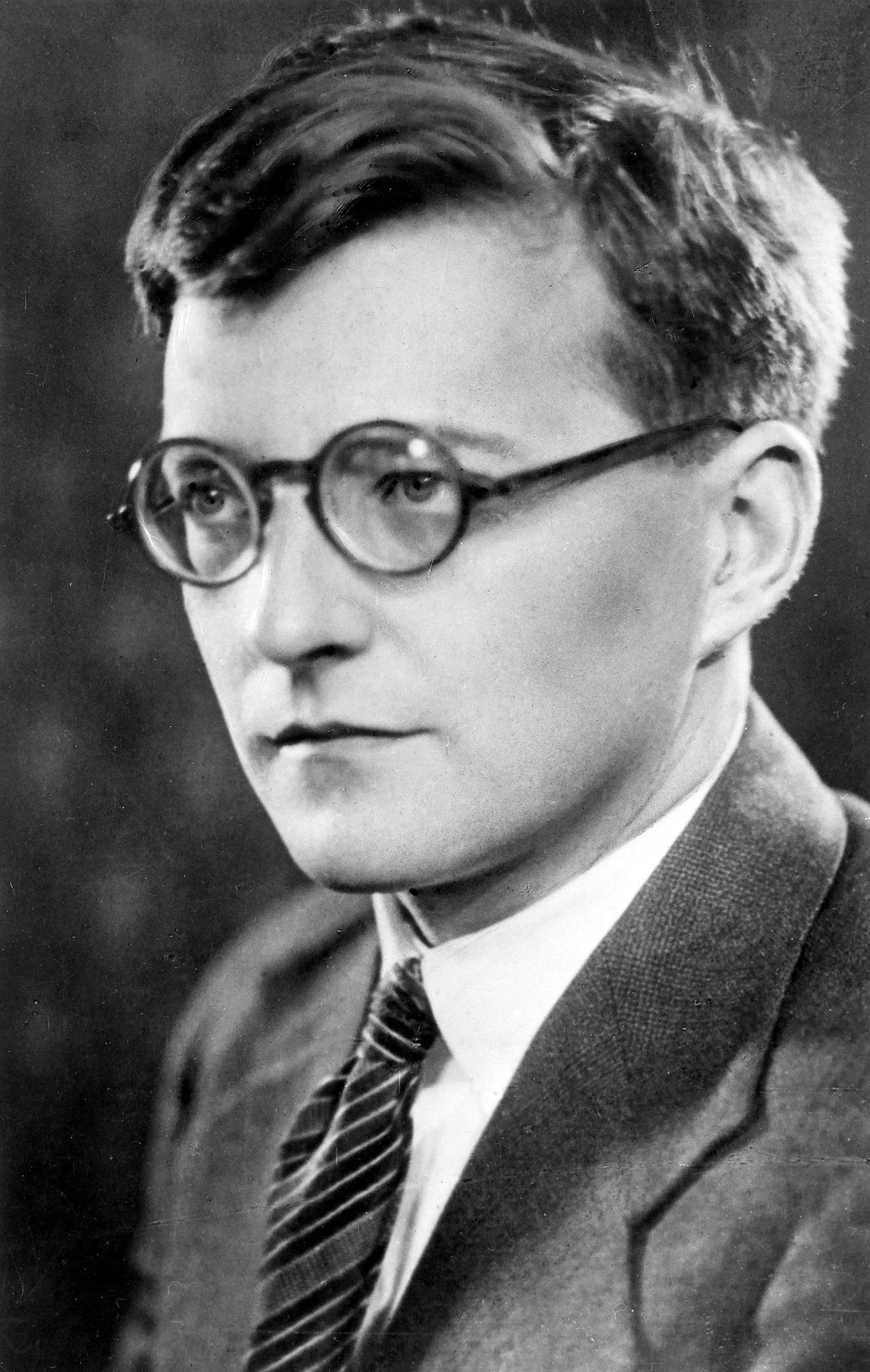

Composer Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

From “young genius” to “enemy of the state”

Composer Dmitri Shostakovich burst on to the scene with his First Symphony, premiered by the Leningrad Philharmonic in 1926 under the baton of Nicolai Malko. Shostakovich was 19, his work composed as a graduation exercise from the St Peterburg Conservatory, yet the musical voice it revealed was already mature, confident and dramatic. The symphony was acclaimed at once, the slight, shy composer receiving a tumultuous ovation after its first performance. The brilliant Scherzo from the symphony was encored that night and the work picked up internationally in short order by big name orchestras and conductors. It was an extraordinarily auspicious debut.

The young Shostakovich

“…an auspicious debut with his First Symphony aged 19.”

In April, Orchestra Wellington gave an incisive performance of the work under conductor Marc Taddei. In the opening minutes, we found ourselves immediately in Shostakovich’s distinctive sound world. A duet between solo trumpet and bassoon develops into chromatic and angular melodic entries from colourful brass and winds, with pizzicato strings on tiptoe and spiky assertive fragments of conversation. The atmosphere, urgent, fast-forward, a little sardonic, brought us to the edge of our seats.

Taddei and Orchestra Wellington were the first of three New Zealand performing ensembles to announce a substantial 2025 tribute to Shostakovich, marking 50 years since his death in 1975. Taddei, always a story-teller, has called the season “The Dictator’s Shadow”, programming the first five of Shostakovich’s 15 symphonies and a suite from his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. The season title refers to the impact on the first fifteen years of Shostakovich’s composing career of Joseph Stalin’s reign of terror.

Why does Taddei believe we should mark this 50th anniversary? Referring to the huge interest from musicologists and scholars after his death, Taddei says Shostakovich is “without question the most important modernist composer. He so clearly represented his culture – and the vagaries of that culture. The triumph of the Revolution, trading one dictator for another, navigating the politics of all of that and the endless communist committees. His music represents all those things.”

Born in 1906, Shostakovich grew up in St Peterburg in a musical family and showed early talent, just 13 year old when he entered what was then the Petrograd Conservatory to study under Glazunov. His father died of pneumonia just a few years later, during difficult times in the city, and Shostakovich’s mother took on menial work to keep him at his studies. As a teenager Shostakovich, already an outstanding pianist, played for silent movies to contribute to the family income.

After the success of the 1st Symphony, the Propaganda Department of the State Publishing House commissioned a symphony from Shostakovich to mark the 10th anniversary of the 2017 “October Revolution”. Although Stalin was establishing his dictatorship, artists in Russia were aware of international modernist trends and still able to experiment. Shostakovich knew of the music of Schoenberg and Bartók, and had heard Berg’s Wozzeck, and his status after the First Symphony as a young genius made him, at least temporarily, something of a darling of the Soviet authorities. They did, however, insist that in fulfilling the commission he must include a poem by the officially sanctioned poet Aleksander Bezymensk.

Orchestra Wellington performed the New Zealand premiere of Shostakovich’s Second Symphony ‘October’ in early June. It’s a peculiar work, described from the stage by Taddei as “bonkers”. It begins with modernist and confusing counterpoint, very quiet at first and gradually emerging from dark, murky mists to a section of what the composer called “ultra-polyphony”, perhaps illustrating revolutionary chaos. A hand-operated siren from the percussion section evokes a factory whistle, calling to the workers. The large choir then sings Bezymensk’s patriotic poem, which Shostakovich apparently hated, and may have been mocking. The full-voiced Orpheus Choir sounded magnificent and in spite of the odd juxtapositions of ideas in the work, it was a strangely coherent and satisfying performance.

Shostakovich seems even more openly sarcastic in the poetry he chose for the choral section for his Third Symphony, ‘The First of May’, scheduled for Wellington performance in late July. Until this point, he seemed to be getting away with his ironic tone and grotesque musical humour, writing film music and exploring modernist ideas in his first opera The Nose, based on Gogol’s absurdist story. The Politburo, however, were not happy with the opera and terms like “formalism”, implying “western” and “decadent”, began to be used about his music. Since Lenin’s death in 1924, Stalin’s power had increased and Shostakovich was no doubt aware of the risks of moving from “favoured son” to “enfant terrible”.

The 1930’s became a difficult time for him. His opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk was premiered in 1934, initially to acclaim. Shostakovich was by then an international star composer and, as well as some 50 performances in Leningrad, Lady Macbeth was performed in America in Cleveland, New York and Philadelphia, along with productions in Buenos Aires, Prague, Stockholm, London and Zurich.

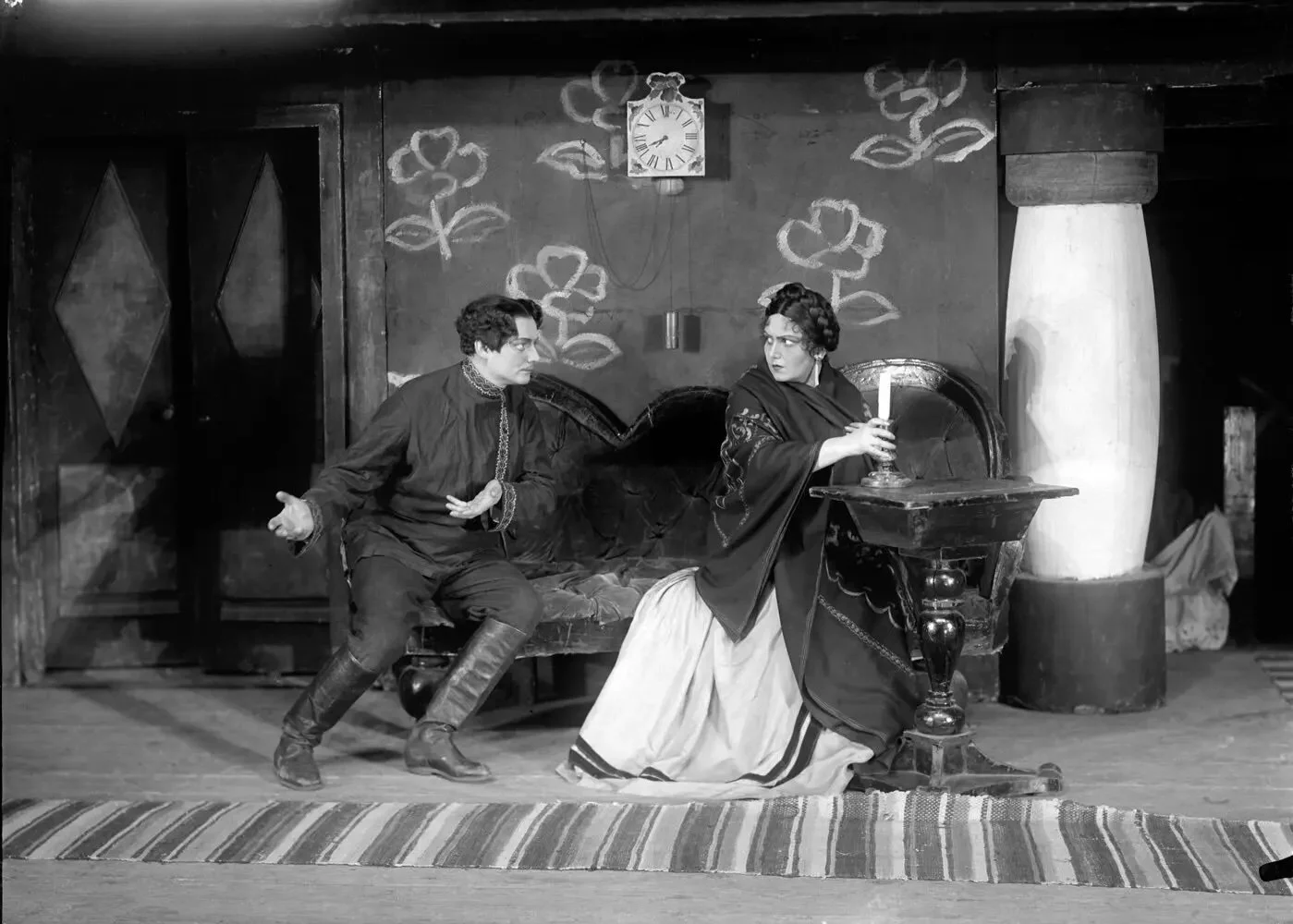

A scene from Shostakovich’s opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk

“…Stalin’s reaction probably changed the course of Shostakovich’s career.”

Disaster struck two years after the premiere when Stalin decided to check out this popular opera in Moscow at the Bolshoi Theatre. Shostakovich was expected to attend. The Bolshoi is a large theatre, and the orchestra was enlarged to suit the venue. Stalin and his entourage were seated in the government box immediately above the brass and percussion. Driven out by the volume, if not the content and musical language, they left before the end. When the composer saw the empty government box, he knew he was in trouble.

The famous critical article that followed in Pravda, “Muddle instead of Music”, probably changed the course of Shostakovich’s career. “This is a game,” the scathing editorial ended ominously, “that might end very badly.” He was denounced by the authorities, became an “enemy of the state” and withdrew his uncompromising, fierce and sometimes downright terrifying Fourth Symphony, already in rehearsal. It remained in a drawer until 1961, well after Stalin’s death. He never completed another opera.

Scenes of Shostakovich waiting with his suitcase packed for the dreaded knock at the door are described in various sources. This was a dark time for those who fell from favour. Large numbers disappeared, sent to the gulag or executed, including some of Shostakovich’s friends and colleagues. His justifiable fears were based on the reality of Stalinism and the possible consequences for himself and his family.

The story being told in Orchestra Wellington’s 6-concert series includes a suite from Lady Macbeth, arranged by Taddei and including the opera’s overture, orchestral interludes and the arias of the soprano heroine, to be sung by Madeleine Pierard. The series ends with his Mahlerian Fifth Symphony, Shostakovich’s attempt to achieve rehabilitation. The latter is perhaps his most popular work, and although he probably didn’t pen the words often linked with the work, “a Soviet artist’s response to just criticism”, there is little doubt that it was composed with a return to favour with the authorities in mind.

And yet, was this magnificent Symphony merely a capitulation to the regime? As British journalist and author Ed Vulliamy wrote in the Guardian “the censors and party cronies at the premiere in 1937 heard a penitent return to classical style after a terrifying reprimand for experiments in modernism, while the audience heard Shostakovich's searing requiem for the victims of Stalin's great terror. This high-wire act would come to characterise Shostakovich's public music, as he condemned himself to a life on the rack.”

I’ll come back to that “rack”, if indeed it is the right image. But first, let’s consider Shostakovich’s chamber music.

Chamber music: the story of a soul

The fledgling Wellington Chamber Music Society (WCMS), formed as World War 2 entered its final stages by local music enthusiasts, with the influential assistance of European refugee Fred Turnovsky, held its second concert in June 1945. On the programme was Shostakovich’s First String Quartet, composed just seven years earlier in 1938, a mere two years after the crisis of Lady Macbeth and his subsequent denunciation. It was a bold programming choice.

In April this year, marking the 80th anniversary of the Society, Shostakovich’s First Quartet was heard again, played by the New Zealand String Quartet in a Sunday afternoon concert for the WCMS. Shostakovich apparently said that in this work he had "visualized childhood scenes, somewhat naïve and bright moods associated with spring."

When he wrote it, he was almost 32, his second child had just been born, he had survived the Lady Macbeth traumas of the previous years and had success with his Fifth Symphony. His first foray in the string quartet medium is a neo-classical work, looking back to 18th century models. On the surface it is light and innocent with little of the irony and dissonance heard in his First Symphony. In the hands of the NZSQ, it proved a charming piece, without the sardonic edge of his later quartets.

Next week in Wellington the Quartet will present the first of four programmes in its “Shostakovich Unpacked” series, curated programmes which include a selection of the composer’s string quartets and other chamber works, alongside compositions by composers of Aotearoa responding to the legacy of Shostakovich while considering his contemporary relevance.

Shostakovich

“…a ‘towering figure’ of the quartet genre.”

Gillian Ansell, the Quartet’s violist, describes Shostakovich as a “towering figure” of the quartet genre, comparing him to Beethoven and, in the 20th century, Bela Bartók. She finds his textures particularly interesting. “He is so much more transparent and sparse than so many other composers in the genre. The texture is never crowded. There might be opposing ideas simultaneously, but it’s never overwhelming or confusing. He doesn’t write a spare note – he’s very communicative, very direct emotionally.”

Shostakovich’s writing for strings “goes through the gamut of what’s possible on the instruments”, says Ansell. “ It’s often really edge-of-the-seat stuff, really enthralling, scary and exhilarating. You’re skiing downhill at a million miles an hour and then, suddenly, it’s super-poignant and desperately tragic, and then uplifting. It’s a joy to tackle, really satisfying.”

Shostakovich wrote 15 string quartets over the course of his life, and it is often asserted that it is in these that his true thoughts and feelings are expressed. “In a little quartet among friends, you can be more honest,” he said once. His widow characterised the quartets as “a diary, the story of his soul."

A third ensemble in Wellington is featuring Shostakovich in a new concert series. Violinist Helene Pohl and cellist Rolf Gjelsten, former members of the NZ String Quartet, have gathered a group of fine professional musicians together as the Chamber Pot Pourri Ensemble and their Saturday afternoon “Comfy Concerts” are presenting a selection of Shostakovich’s string quartets, complementary to those in the NZSQ “Unpacked” series.

“There’s something about this music,” says Pohl, “that has very high aspirations. It’s not music for entertainment, it’s music that has meaning.” In the 1990’s Gjelsten and his colleagues met the Shostakovich Quartet, an ensemble formed at the Moscow Conservatory and named after the composer. “They said,” he recalls, “that this music is an emotional history of all of them. Shostakovich absolutely got how they were feeling under the regime.”

Like Ansell, Gjelsten and Pohl are struck by Shostakovich’s use of texture in his quartets to illustrate his feelings and thoughts. “Often, he uses a scenario where three musicians are playing some kind of background that sets a mood, maybe threatening or sometimes very beautiful, and the fourth musician is playing something completely different, responding to that atmosphere” says Gjelsten. “He’s expressing a layered society, where one person is on the outside, trying to deliver a message. Shostakovich can be sarcastic about the communal expression, but not about the individual voice, which is expressing the truth. That’s where the politics and the musical form come together.”

Pohl, who as 1st violinist is often that isolated individual in the texture, makes an interesting point about interpretation. “A sense of constriction, fear or dread sometimes comes into play musically; the rhythm just keeps on going and you have to work within it. Shostakovich is the composer for whom rubato should be used most sparingly. That flexible approach is important in so much music, romantic or classical, but in Shostakovich’s music, it weakens the expression.”

In the first of their four “Unpacked” concerts, the NZ String Quartet will join with musicians from Orchestra Wellington and the young Antipodes Quartet for Shostakovich’s Chamber Symphony in C minor. It is in fact a transcription for a larger ensemble of his Eighth String Quartet, an intense and searing work that has become the most-often played of the whole quartet cycle. It will be played in its original quartet form by the Pot Pourri Ensemble in September.

The dark, burning anguish and tragic power of the Eighth Quartet are sometimes associated with Shostakovich’s reaction to the destruction of the beautiful baroque centre of Dresden by an infamous Allied bomb attack in February 1945. He wrote the work in three days while housed near Dresden, officially there to compose music for the Soviet film about the city’s ruin, 'Five Days - Five Nights'. In the USSR the Eighth Quartet was referred to as the “Dresden Quartet”.

Shostakovich gave it a dedication: 'In Remembrance of the Victims of Fascism and War'. As in so much of his music, his intentions were ambiguous. He referred to the work as autobiographical, and wrote it at a time when he was reportedly in despair, even, according to some reports, suicidal.

The autobiographical interpretation carries some weight when we consider that, from the first bar, he has woven a motif based on his own initials throughout the quartet, D, E-flat, C and B. (In German musical notation these notes are written as D, S, C, and H.) He uses the motif elsewhere in his compositions, notably in his Tenth Symphony, and in this quartet also quoted some of his other works, consistent with the idea that he was writing about his own troubled life.

Shostakovich was married three times and grief for his beloved first wife Nina may have contributed to his despair during his time in Dresden. After his death he was buried near Nina, and the DSCH musical motif appears on a stave on his gravestone at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.

Shostakovich’s grave in Moscow

“..the musical motif based on his initials DSCH is on his gravestone.”

Towards the end of his life, Shostakovich became obsessed with his own mortality. His health deteriorated rapidly in his 60’s. A chain smoker of unfiltered Russian cigarettes, he had dealt with high levels of stress and was reportedly highly strung and often nervous in public. He and his wife Irina travelled to the West, first for performances and an award in Copenhagen, and then to the States, where he consulted, as planned, American doctors about his multiple health conditions. They confirmed the findings of Soviet doctors that his illnesses were incurable.

Shostakovich continued composing until the very end of his life, in spite of the many miseries of his poor health. He had apparently planned to write 24 string quartets, one in every key. He did not live to achieve this goal but his 15 quartets are in many ways the pinnacle of his achievements and the music in which we hear his most profound and personal expression.

In November Wellington chamber music audiences will hear two of his final works. The final Comfy Concert programme includes his deeply moving, almost desolate Fifteenth String Quartet, six linked movements, all in the key of E flat minor, all marked Adagio, the first an Elegy, the fifth a Funeral March, the last an Epilogue.

There seems no doubt that Shostakovich knew that this was his final string quartet. And yet his wry humour was present when he advised the performers to “play the first movement so that flies drop dead in mid-air and the audience leaves the hall out of sheer boredom.”

His last work, virtually from his deathbed, will end the NZ String Quartet’s final ‘Unpacked’ concert in November. Ansell and pianist Jian Liu will play his Sonata for Viola and Piano, completed a month before Shostakovich’s death in August 1975. It was written for and dedicated to Fyodor Druzhinin, violist of the Beethoven Quartet and a musician close to the composer.

Shostakovich, who wrote the Sonata at his dacha before being admitted to hospital for the last time, told Druzhinin “the first movement is a novella, the second a scherzo and the Finale an adagio in memory of Beethoven.” This poignant work again contains an autobiographical and elegiac expression, with quotes from several of Shostakovich’s own compositions, including a youthful work originally dedicated to his father and an excerpt from his unfinished 1942 opera The Gamblers.

The Viola Sonata’s reference to Beethoven, including an allusion to the ‘Moonlight’ Sonata, seems particularly significant for the final movement of Shostakovich’s last composition. Like Beethoven, Shostakovich wrote music for “the people”, music of enormous humanity, which continues to communicate long after his death. For this complex and often conflicted man, the most internationally renowned Soviet composer of the 20th century, it is his music that provides the most compelling insight into his life, his thoughts and the cultural context in which he worked. The enormous variety in that music shows us the many sides of the composer and the man.

The “Shostakovich Wars”

When Shostakovich died in a Kremlin-run hospital in Moscow in 1975, aged 68, the New York Times in its obituary quoted without irony a Leningrad literary journal: “Shostakovich's personality and life are not well known to us — it is not a question of his life, which was uneventful, but the inner biography of the man.”

From our perspective today, just 50 years later, those words seem astonishingly off beam. But we now have the writings of a veritable army of musical critics, biographers, scholars and journalists, drawing our attention to not only the enormous oeuvre of this giant of the 20th century, but the way the music itself tells the “inner biography of the man”.

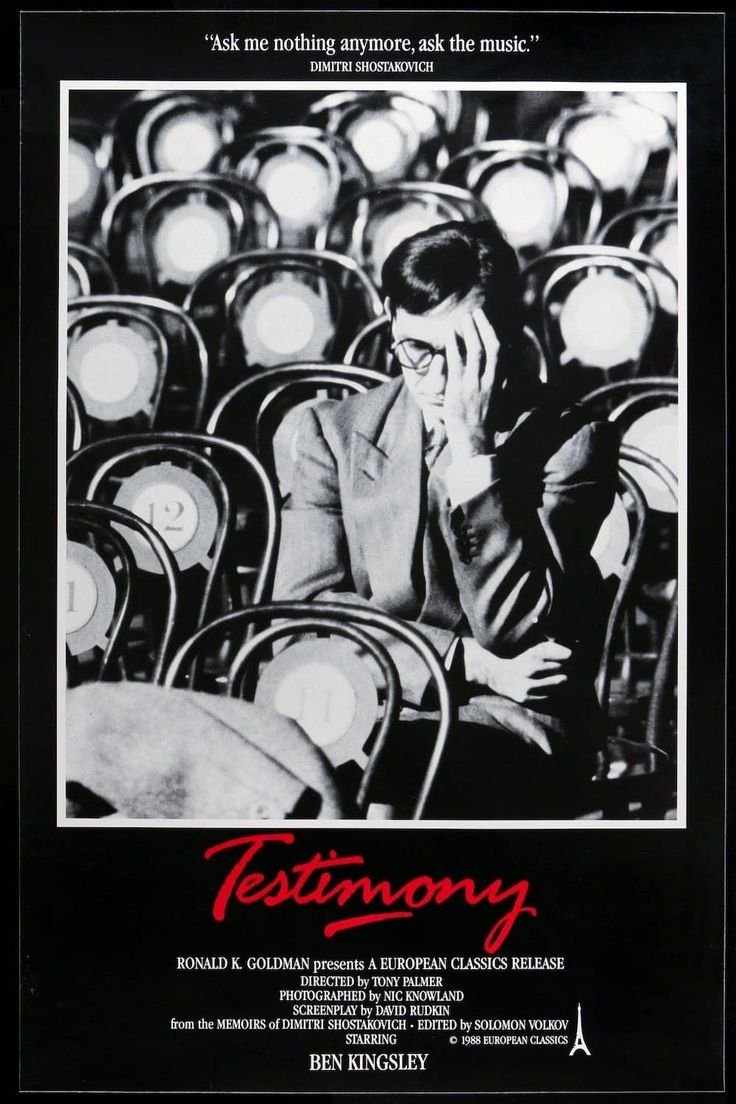

The now famous “Shostakovich Wars” began a few years after his death with the publication in 1979 of Testimony: the memoirs of Shostakovich “as related to and edited by Solomon Volkov”. Volkov, a Soviet musicologist, was just 16 when he reviewed the 1960 premiere of Shostakovich’s Eighth String Quartet for a Leningrad newspaper and met the composer. As a devoted fan, he spent many years studying Shostakovich’s music. In the Preface to Testimony Volkov describes how he also met with Shostakovich over many years to record his memoirs, eventually realising they could not be published in Russia and taking the manuscript to the West.

The publication of Testimony, which later became a film, created a furore in Moscow

…and a different storm amongst scholars in the West.

Testimony created a furore in Moscow, blowing apart the official view of Shostakovich as an artist loyal to the Soviet regime. The picture it painted, purportedly in Shostakovich’s own words, was of a cynical composer who appeared to support the official line while writing music that revealed his true feelings. Some of that music had not been performed in his lifetime.

As the most famous Soviet composer, he was an important symbolic figure. In 1960 he had, albeit reluctantly and possibly with some cynicism, joined the Communist Party, a move necessary for him to accept Khruschev’s offer of the leadership of the new Russian Composers’ Union. He had received the prestigious Stalin Prize several times for his compositions and was very active in public life.

Volkov and his book were predictably denounced and banned in Russia. In the West, still in the grip of Cold War struggles and tensions, Testimony created a different kind of storm, particularly among American scholars, leading to a huge reappraisal of Shostakovich’s music and the relationship between his massive oeuvre and his unpredictable and sometimes tortured relationship with the authorities.

Many more volumes and articles have been written since about Shostakovich, while Testimony has continued to sell in 30 languages. Some close to the composer, musicians and family members, affirmed that Volkov had captured the composer’s authentic voice; others, including respected scholars, doubted the work’s provenance and have attempted to discredit the author. Novelist Julian Barnes created a semi-fictional book, The Noise of Time, a captivating portrait of Shostakovich based on both Testimony and a more recent and perhaps more credible source, Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, by Elizabeth Wilson.

The “Shostakovich Wars” may have ended with the publication of Pauline Fairclough’s biography Dmitry Shostakovich in 2019, a more nuanced account which acknowledged some of the conflicts and stress he undoubtedly experienced under his Politburo overlords, without over-emphasising his role as a hero of the resistance, hiding coded messages in his music.

It is not an easy matter to sum up this complex composer. Reports of his cheerful, joking friendship with the Beethoven Quartet, who premiered 13 of his quartets, suggest there were happier times than implied by numerous images of him frowning, turning grimly away from the camera, cigarette in hand. His reported trembling at public events contrasts with joyous photos of him at the football matches he described as “the ballet of the masses.”

A rare smiling image of Shostakovich

“…he loved football, describing it as ‘the ballet of the masses’”.

And of his role in the Soviet Union? Was Shostakovich a dissident within the Soviet state, writing ironic music with secret meanings, as Testimony suggests. Or was he a compliant and loyal supporter of the Party who wisely toed the line in his compositions and his public speeches?

Does it matter? “Art,” said Shostakovich, “should be addressed to the people.” Let the audience decide.

Orchestra Wellington Marc Taddei (conductor) “The Dictator’s Shadow”. Upcoming 7.30pm concerts on 26 July, 20 September, 18 October, 22 November 2025. More information and tickets here

New Zealand String Quartet Shostakovich: Unpacked. Upcoming Wellington concerts on 9 July, 6 August, 1 October and 25 November 2025. Auckland concert 24 September. More information and tickets here (for Wellington) and here (for Auckland)

Chamber Pot Pourri Ensemble Comfy Concerts at the Long Hall, Wellington. Upcoming 4pm concerts 30 August, 20 September, 18 October, 15 November 2025. More information and tickets here