Immerse Festival: NZSO’s next Music Director reveals his strengths

André de Ridder, Music Director Designate of the NZSO, during the Immerse Festival in Wellington

Image credit: NZSO/Latitude Creative

Under the baton of German conductor André de Ridder, the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra sounded crisp, precise and colourful in the opening of their annual mid-winter Immerse Festival. Large forces were assembled for the programme, which began with Rimsky-Korsakov’s orchestration of the nocturnal terrors of Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain.

De Ridder has been announced as the NZSO’s next Music Director, taking up the role in 2027. This is a big deal. The last conductor to hold the title was Edo de Waart, who ended his tenure in 2019. Before him in the role were Pietari Inkinen and James Judd. New Zealander Gemma New was appointed as NZSO Artistic Adviser and Principal Conductor in 2022 and will step aside when de Ridder takes up the Music Director role, retaining her relationship with the NZSO with the unusual title of Artistic Partner.

This visit is de Ridder’s fourth to New Zealand and third with NZSO. Conducting three-concert Immerse Festivals in 2023 and 2024, he impressed with his boundary-crossing versatility, fine, coherent performances of classical repertoire, accompanying skills in concertos and fresh, energetic, and well-paced interpretations. He has also shown himself to be a relaxed and genial communicator with excellent rapport with the NZSO musicians.

These are all great qualities in a Music Director, a role which also implies responsibilities for artistic decision-making, including repertoire choices. The first Immerse programme in 2023 included Become Ocean by John Luther Adams, bold programming which was indeed immersive and fascinating. Since then, the “Immerse” brand has seemed less relevant to the mid-winter grouping of three concerts over two weekends in Wellington and Auckland.

Audiences were rather sparse for the first two Wellington concerts of this year’s festival. The NZSO’s new Chief Executive, American Marc Feldman, introduced the first programme from the stage with the unfortunate descriptor ‘Fantasia revisited’, noting that de Ridder had chosen the repertoire.

Mussorgsky’s work was followed by Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Without Disney’s cartoon to illustrate this programmatic and playful work, it proved pretty simplistic, four-square stuff. The contrabassoon makes a hilarious appearance and the whole talented bassoon section was fine under the musical leadership of Justin Sun. De Ridder demonstrated his excellent dramatic and musical timing, but this kind of programming sadly underestimates the Wellington audience, many of whom seem to have stayed home.

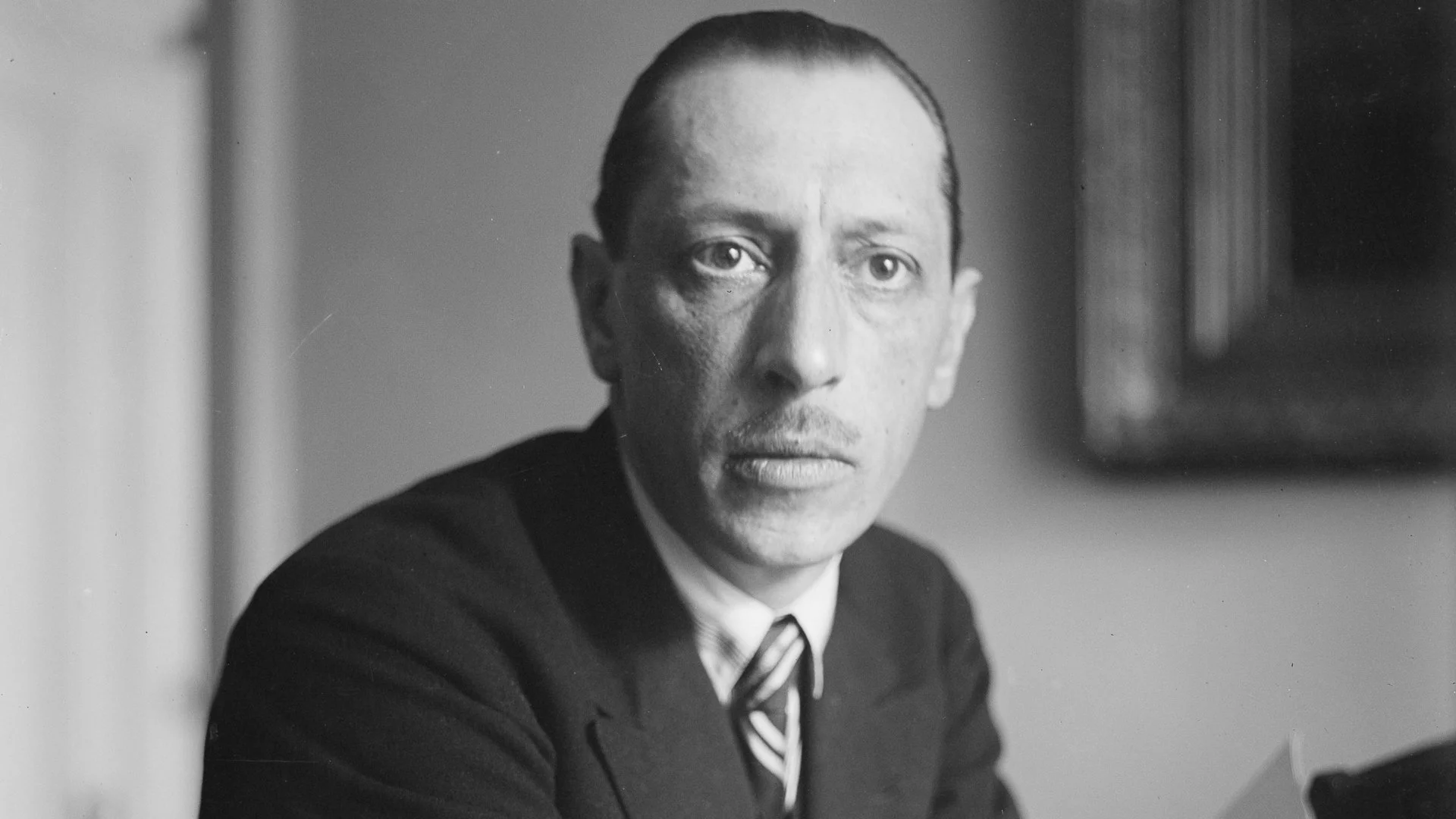

Igor Stravinsky

“…astonishing orchestration and energetic rhythmic invention.”

Image credit: Library of Congress

Fortunately this “Enchanted” concert was saved by Stravinsky’s masterpiece Petrushka, an orchestral suite from his 1911 ballet score for Diaghilev, created by the composer in 1946/7. De Ridder offered a nicely humorous introduction to the performance, revealing his obvious fondness for the orchestra, and pointing out the link between this story of a sorcerer bringing a puppet to life and the two previous works in the programme.

The whole “Enchanted” programme showcased all sections of the Orchestra, and Petrushka does this marvellously with astonishing orchestration and Stravinsky’s energetic rhythmic invention. We travelled from the busy colour contrasts and carnival atmosphere of the ‘Shrovetide Fair’ to acidic bitonal flavours as the puppet dances in ‘Petrushka’s Cell’, then on to oriental colours and rhythms in the ‘Moor’s Room’ and back to the Fair after dark, the work dancing to its poignant and witty conclusion, the ghost of Petrushka floating whimsically on the rooftop.

In ‘Petrushka’s Cell’

“…acidic bitonal flavours as the puppet dances with the Ballerina.”

The NZSO’s performance of Petrushka was terrific. We could not forget that the work is a ballet, de Ridder almost dancing on the podium. Individual solos and section work were marvellous – Bridget Douglas’s gorgeous flute solo in Petrushka’s cell, guest pianist Justin Bird explosive and dramatic throughout, muted trumpets and trombones intense in the Moor’s Room, more lovely wind solos back at the night-time Fair, strings sections full of energy and colour and percussion and timpani always on point. De Ridder’s timing and pace were impeccable, and he managed the many layers of Stravinsky’s sophisticated textures with flexible ease.

The Immerse Festival coincided with an exceptionally cold, wet winter blast in Wellington, a southerly storm arriving on Friday night and a bitter wind blowing all weekend. The spring-like themes of the second Immerse concert, with birds aplenty, provided a welcome contrast.

The “Ascension” concert was no doubt named with Vaughan Williams’ famous The Lark Ascending in mind. The audience was quietly entranced by the exquisite lyricism of concertmaster Vesa-Matti Leppänen’s playing of the solo violin part of this perennial favourite. He dedicated his performance to Sir Michael Hill, the arts philanthropist who died recently, and played the work on his Guadagnini violin, which was previously owned by Sir Michael. I find the piece, which de Ridder conducted with low-key restraint, a little cloying in its syrupy romanticism, but it is without doubt beloved by audiences, and there was a pin-drop silence as Leppänen held the mood before appreciative applause.

Taonga pūoro musician Jerome Kavanagh Poutama

…co-composer with Salina Fisher of Papatūānuku.

Image credit: NZSO/Latitude Creative

Papatūānuku, the undoubted highlight of the evening, was created collaboratively by co-composers Salina Fisher and Jerome Kavanagh Poutama. Commissioned and premiered by the Auckland Philharmonia in 2023, the work was played earlier this year by both the Christchurch Symphony Orchestra and the Thessaloniki State Symphony Orchestra in Greece.

An educator and expert performer on taonga pūoro (Māori traditional instruments), Poutama introduced the fascinated audience to the 19 instruments he would play in the work, including pōrutu pounamu (greenstone flute) and kōauau (small flute), the birdcalls of the karanga manu and karanga wekaweka, the pūtorino , a bugle flute, a whirler made from harakeke (flax), the pūtātara (made from a conch shell) and tūmutūmu, tapping instruments of wood and stone.

The work, in Fisher’s words, “honours Papatūānuku (earth mother) as the bearer of all life, and centres instruments/voices that are closely connected to the natural world. It also honours the interconnectedness between wāhine (women) and whenua (land, placenta), recognising te whare tangata (the house of humanity) as both the womb of a woman, and womb of the earth.

Papatūānuku is perhaps the most effective integration of taonga pūoro with the western classical orchestra I have heard. Poutama improvises on the instruments, creating moving melodies and dramatic sounds, and Fisher’s skilful orchestration weaves the orchestral fabric around his playing. We start in the depths, with drum, lovely piano lines and low strings, Poutama playing the pōrutu pounamu, the music growing organically in strength and dynamic. There’s a haunting quality as an ancient melody is combined with solo cello and viola, percussion quietly underneath, timpani rolling gently. Flute, horns, tuned percussion and trombones emerge from the texture, taonga pūoro soaring above. The effect is simultaneously large and quiet, the performance almost reverent under de Ridder’s careful direction.

Composer Salina Fisher

“…her Papatūānuku, co-composed with Jerome Kavanagh Poutama, is a highly effective integration of taonga pūoro with the western classical orchestra.”

Then the birds arrive, karanga manu and other bird-like taonga pūoro, skilfully played by Poutama as the orchestral instruments flutter around him with a chorus of tweeting. There’s beautifully inventive writing for the violins and harp, then flute, oboe and xylophone, the tapping of the tūmutūmu against the orchestral chorus. Poutama, rubbing stones together, sings in Gaelic, acknowledging his Irish heritage, before deep timbres sound from both orchestra and taonga pūoro, as if the earth itself is breathing.

The final section of the work is particularly compelling, a strong call on the pūtātara blending with drama from the trombones, flourishes from the harp and the whole orchestral fabric swelling, before final chanting and the almost human sound of the pōrutu pounamu with which the work begins.

The audience was enthralled throughout, and, after a rapt silence, gave Papatūānuku a great ovation, many standing to acknowledge the creators and the performers. The kotahitanga (“togetherness”) of the project was deeply moving. Fisher and Poutama have created a major work uniquely of Aotearoa New Zealand, weaving together our Māori and Pākeha cultures, a symbolic composition which could proudly represent us internationally.

The evening ended with Schumann’s 1st Symphony, known as “Spring”, played by an ensemble of classical proportions, at least in the string sections. From the great pompous entry of strings and brass to the nicely paced, light and graceful Finale, de Ridder revealed his characterful conception of the work, communicating it in a relaxed manner to the responsive orchestra. I’m looking forward to the tenure of this fine conductor as NZSO Music Director while hoping he will respond strongly to both our willingness to enjoy adventurous repertoire and the quality of our composers.

Conductor André de Ridder rehearsing with the musicians of the NZSO

Photo credit: NZSO/Phoebe Tuxford

NZSO Immerse Festival: Andre de Ridder (Conductor), Vesa-Matti Leppänen (Violin), Jerome Kavanagh Poutama (Taonga Pūoro), music by Mussorgsky, Dukas, Stravinsky, Vaughan Williams, Salina Fisher & Jerome Kavanagh Poutama and Schumann. Wellington August 8 & 9, 2025.

Both concerts will be performed in Auckland August 15 & 16, 2025.

More details and booking link here.